They continued to survive and grow, thus earning themselves the “immortal” moniker. Her cells did not die once they were separated from her body. Henrietta’s cells are so vital to science because they are the first immortal human cells ever grown in a lab. The first is the literal and physical immortality of Henrietta’s cells. Immortality is another central part of Henrietta’s story, and must be considered from two separate angles. As Gary, Henrietta’s nephew, says near the end of the book, “those cells are Henrietta,” no matter what science or medicine may claim. And when they read about the amazing and life-saving discoveries made because of HeLa, they attribute it to their mother’s generosity and propensity for taking care of others. Rather, they see their mother, wife, and friend being subjected to inhuman physical trials.

So for example, when Deborah and other Lackses read newspapers articles about HeLa cells being crossed with tobacco plants, sent into space, or injected with AIDS and Ebola, they don’t visualize these acts being done to microscopic cells. To them, Henrietta is HeLa, and HeLa is Henrietta. They are the living and sole remaining pieces of their family member on Earth. To them, the HeLa cells are not a separate entity, or merely a culture of cells on a petri dish. The dehumanization of Henrietta is particularly difficult for her family to understand and cope with. In her own words, she had “never thought of it that way” (Pg. During the autopsy when Kubicek sees Henrietta’s painted toenails, they make her realize for the first time that behind the HeLa cells was a real person, a live woman. Mary Kubicek’s reaction when she performs an autopsy on Henrietta’s body is an illustration of this fact. Henrietta ceased being a young, Black mother of five, and instead became the source of a cell line that had the potential to change the world. Neither the scientists who first packaged Henrietta’s cells, nor the thousands of scientists and doctors who would later use her cells for groundbreaking research and medical discoveries, thought about their human source.

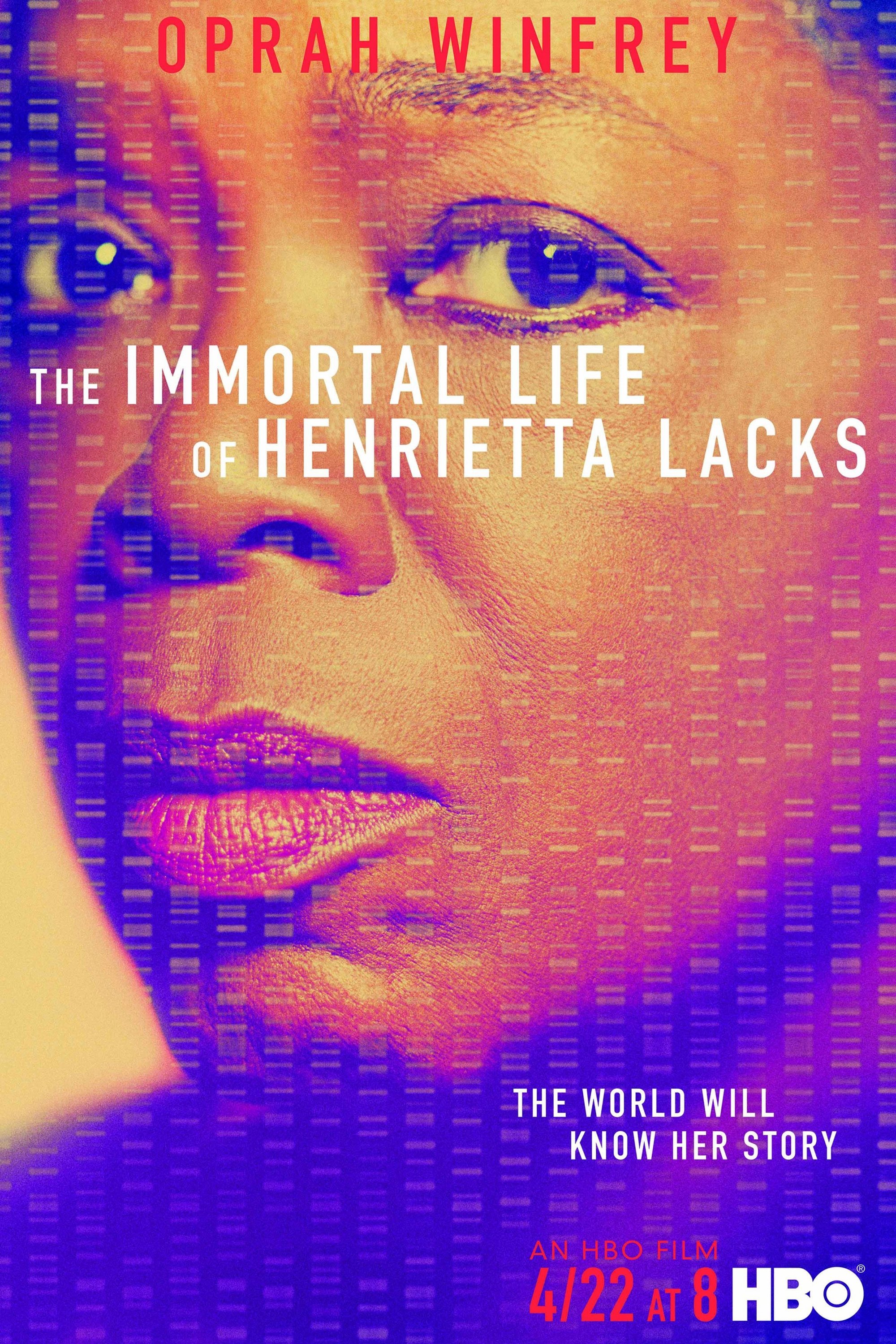

From the moment the Geys discover the incredible ability of Henrietta’s cells, those cells take center stage, and the human whom they originated from is reduced to nothing more than a source. The dehumanization of Henrietta is one of the central themes and storylines of The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. (Feb.Buy Study Guide The Dehumanization of Henrietta Lacksĭehumanization is s a process that undermines and/or strips someone of his or her humanity and individuality. Letting people and events speak for themselves, Skloot tells a rich, resonant tale of modern science, the wonders it can perform and how easily it can exploit society’s most vulnerable people. Writing in plain, clear prose, Skloot avoids melodrama and makes no judgments. Skloot’s portraits of Deborah, her father and brothers are so vibrant and immediate they recall Adrian Nicole LeBlanc’s Random Family. What Skloot so poignantly portrays is the devastating impact Henrietta’s death and the eventual importance of her cells had on her husband and children. These cells have aided in medical discoveries from the polio vaccine to AIDS treatments. They spawned the first viable, indeed miraculously productive, cell line-known as HeLa. Without her knowledge, doctors treating her at Johns Hopkins took tissue samples from her cervix for research. Henrietta Lacks was a 31-year-old black mother of five in Baltimore when she died of cervical cancer in 1951. Science journalist Skloot makes a remarkable debut with this multilayered story about “faith, science, journalism, and grace.” It is also a tale of medical wonders and medical arrogance, racism, poverty and the bond that grows, sometimes painfully, between two very different women-Skloot and Deborah Lacks-sharing an obsession to learn about Deborah’s mother, Henrietta, and her magical, immortal cells.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)